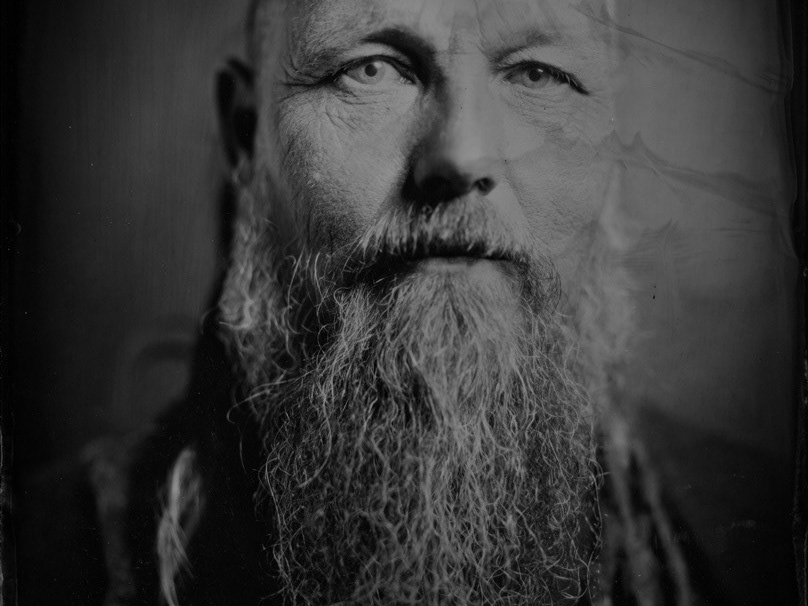

With each portrait I create in Alchemy Studio, I unveil a visual narrative that serves as an exquisite invitation to a journey through time, transporting the beholder to the mid-19th century. In this era of splendor, photographers, true artists and alchemists, explored the intricate secrets of chemistry to immortalize images.

We witness a glorious era in the popularity of photography, just three decades after its invention. The most revered format for portraits was the remarkable "Tintype," so named due to its metal plate support. The chemical process, known as "Wet Collodion," was masterfully conceived in 1851 by Frederick Scott Archer, a visionary English sculptor.

Immersed in this unique period, the subjects actively participate in the entire process, from the meticulous application of the emulsion to the metal plate to the magical moment when the image emerges, revealing itself from chemistry as an artistic manifestation.

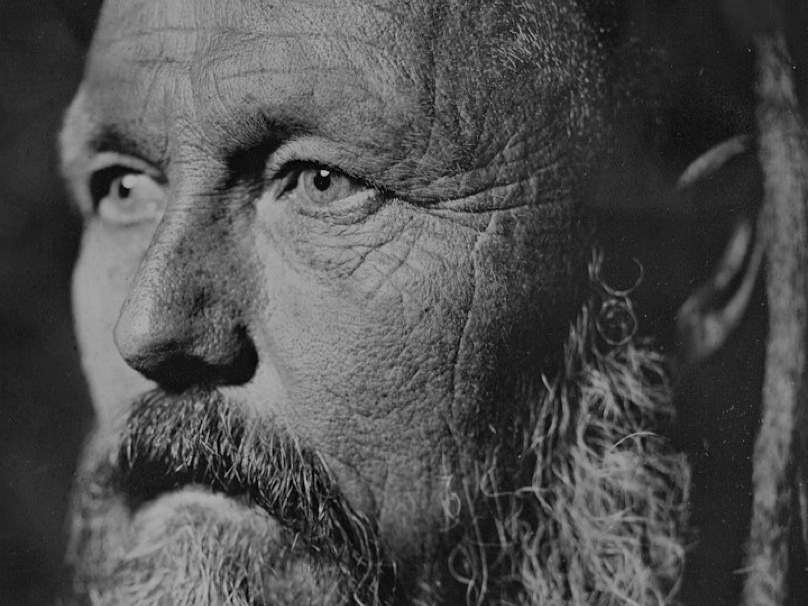

Each portrait, a masterpiece that requires about 40 minutes to be meticulously crafted, results in a singular and inimitable visual representation, skillfully engraved on a metal plate. At Alchemy Studio, we provide not only portraits but a magical and unforgettable experience, where the alchemy of photography transcends the ordinary, celebrating art and history in a unique way.

The intrinsic complicity in committing to a process that doesn't unfold as instantly and post-controllably as contemporary ones elicits remarkably intense expressions in the subjects. They are exposed without artifice, immortalized viscerally on a metal plate.

This intensity is evident in each portrait, a depth that imparts a unique soul to the moment. Each image fulfills the distinct characterization I assign to it, in a magical symbiosis blending the hyper-realism of large-format photography with imperfections arising from various chemical reactions. This transforms each portrait into a piece as unique as the individual portrayed.

Undoubtedly, it represents a hyper-realistic metaphor of human experience. For me, it's an act of participating in the eternalization of someone through the creation of a physical, singular, and everlasting object. It's as if we are witnessing a 19th-century "tintype," an intimate fragment of history, immortalized in a uniquely and profoundly significant way.

In the past decade, I have immersed myself deeply in the practice of wet plate collodion, a fascinating photographic process. Throughout this journey, I have traveled to artistic residencies, portrait sessions, productions for grants, and collaborations with various institutions and museums. I've set up temporary studios in diverse contexts, privileged to capture thousands of people on metal plates.

This experience has led me to a substantial mastery of this process. However, even with this accumulated expertise, each portrait I conceive continues to pose a significant challenge for me.

My connection with this process goes beyond the simple act of taking photographs. In a dance between light and chemistry, I engage in a constant quest for solutions. At times, this leads me to question the entire process. Its fragility demands the creation of a thought process constantly besieged by inquiries. I seek to interpret the final result, guided by the visual aspect of each chemical reaction. This ongoing exploration contributes to a reflective approach and the constant refinement of my artistic practice.

Frederick Scott Archer

(Bishop's Stortford, 1813 - 1857)

Frederick Scott Archer, beyond being a sculptor, revealed himself as a visionary photographer and inventor. Recognizing the utility of calotype photography in capturing images of his sculptures, Archer, dissatisfied with the limited definition, contrast, and long exposures required, brought to life the wet plate collodion emulsion in 1848 in London. This revolutionary method replaced pioneering photography processes like the daguerreotype and calotype.

Archer introduced his innovation to the world in 1851 through publication in the "The Chemist" magazine. Consciously, he chose not to initially patent his creation, considering it a gift to humanity.

Archer's envisioned process involved a solution of pyroxylin in ether and alcohol, enriched with a modest soluble and a certain amount of bromide. This mixture was applied to a glass or metal plate. In the darkroom, the ionized collodion, immersed in a silver bath, formed silver iodide with excess nitrate. The plate, still wet, was then exposed to light in the camera, developed by immersion in pyrogallol with acetic acid, and fixed with sodium thiosulfate.

Archer's most remarkable legacy lies in this singular achievement, significantly broadening the accessibility of photography to the general public. His legacy extends beyond the technique, reflecting a generous vision that transcended the pursuit of individual recognition, contributing to the democratization of the art of photography.